Strom Thurmond

| Strom Thurmond | |

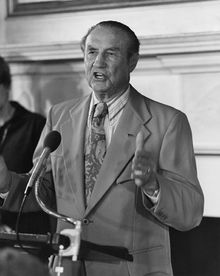

Thurmond in 1977. |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office November 7, 1956 – January 3, 2003 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas A. Wofford |

| Succeeded by | Lindsey Graham |

| In office December 24, 1954 – April 4, 1956 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles E. Daniel |

| Succeeded by | Thomas A. Wofford |

|

103rd Governor of South Carolina

|

|

| In office January 21, 1947 – January 16, 1951 |

|

| Lieutenant | George Bell Timmerman, Jr. |

| Preceded by | Ransome Judson Williams |

| Succeeded by | James F. Byrnes |

|

|

|

| In office January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1987 |

|

| Preceded by | Warren G. Magnuson |

| Succeeded by | John C. Stennis |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2001 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

| In office January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2001 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

|

|

|

| In office June 6, 2001 – January 3, 2003 |

|

| Preceded by | position created |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

|

|

|

| Born | December 5, 1902 Edgefield, South Carolina |

| Died | June 26, 2003 (aged 100) Edgefield, South Carolina |

| Political party | Democratic (1923–1948, 1954–1964) States Rights Democratic (1948–1954) Republican (1964–2003) |

| Spouse(s) | Jean Crouch (1947–1960) (deceased) Nancy Janice Moore (1968–2003) (separated 1991–2003) |

| Children | Essie Mae Washington-Williams Nancy Moore Thurmond James S. Thurmond, Jr. Juliana Whitmer Paul Reynolds Thurmond |

| Profession | lawyer, politician |

| Religion | Southern Baptist |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army United States Army Reserves |

| Years of service | 1942–1963 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II *Normandy Campaign |

| Awards | Legion of Merit (2) Bronze Star with valor Purple Heart World War II Victory Medal European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal Order of the Crown Croix de Guerre |

James Strom Thurmond (December 5, 1902 – June 26, 2003) was an American politician who served as the 103rd Governor of South Carolina and as a United States Senator. He also ran for the Presidency of the United States in 1948 as the segregationist States Rights Democratic Party (Dixiecrat) candidate, receiving 2.4% of the popular vote and 39 electoral votes. Thurmond later represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to April 1956 and November 1956 to January 2003, at first as a Democrat and after 1964 as a Republican, switching parties as the conservative base shifted.

He left office as the only senator to reach the age of 100 while still in office and as the oldest-serving and longest-serving senator in U.S. history (although he was later surpassed in the latter by Robert Byrd).[1] Thurmond holds the record for the longest serving Dean of the United States Senate in U.S. history at 14 years. He conducted the longest filibuster ever by a lone senator in opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1957, at 24 hours and 18 minutes in length, nonstop. He later moderated his position on race, but continued to defend his early segregationist campaigns on the basis of states' rights in the context of Southern society at the time,[2] never fully renouncing his earlier viewpoints.[3][4] After his death, Essie Mae Washington-Williams, born to a young black maid in his parents' employ, revealed Thurmond was her father.[5]

Contents |

Early life and career

James Strom Thurmond was born on December 5, 1902, in Edgefield, South Carolina, the son of John William Thurmond (May 1, 1862 – June 17, 1934) and Eleanor Gertrude Strom (July 18, 1870 – January 10, 1958). He attended Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina (now Clemson University), where he was a member of the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity. Thurmond graduated in 1923 with a degree in horticulture. He was a farmer, teacher and athletic coach until 1929, when he became Edgefield County's superintendent of education, serving until 1933. Thurmond studied law with his father and was admitted to the South Carolina Bar in 1930. He served as the Edgefield Town and County attorney from 1930 to 1938. In 1933 Thurmond was elected to the South Carolina Senate and represented Edgefield until he was elected to the Eleventh Circuit judgeship.

World War II

In 1942, after the U.S. formally entered World War II, Judge Thurmond resigned from the bench to serve in the U.S. Army, rising to Lieutenant Colonel. In the Battle of Normandy (June 6 – August 25, 1944), he landed in a glider attached to the 82nd Airborne Division. For his military service, he received 18 decorations, medals and awards, including the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster, Bronze Star with Valor device, Purple Heart, World War II Victory Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Belgium's Order of the Crown and France's Croix de Guerre. During 1954–55 he was president of the Reserve Officers Association. He later retired from the U.S. Army Reserves with the rank of Major General.

Governor of South Carolina

Thurmond's political career began in the days of Jim Crow laws, when South Carolina strongly resisted any attempts at integration. Running as a Democrat, Thurmond was elected Governor of South Carolina in 1946, largely on the promise of making state government more transparent and accountable by weakening the power of a group of politicians from Barnwell, which Thurmond dubbed the Barnwell Ring led by House Speaker Solomon Blatt. Thurmond was considered a progressive for much of his term, in large part due to his influence in arresting all those responsible for the lynch mob murder of Willie Earl. Though none of the men were found guilty by the jury, Thurmond was congratulated by the NAACP and the ACLU for his efforts.

Run for President

In 1948, after President Harry S. Truman desegregated the U.S. Army, proposed the creation of a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission, supported the elimination of Poll Taxes, and wished to draft federal anti-lynching laws, Thurmond became a candidate for President of the United States on the third party ticket of the States' Rights Democratic Party, which split from the national Democrats over the proposed constitutional innovation involved in federal intervention in segregation. Thurmond carried four states and received 39 electoral votes. One 1948 speech, met with cheers by supporters, included the following:listen

| “ | I wanna tell you, ladies and gentlemen, that there's not enough troops in the army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the nigger race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes, and into our churches.[6] | ” |

Early runs for Senate

Thurmond ran for the U.S. Senate in 1950 against Senator Olin Johnston. Both candidates denounced President Truman during the campaign. Johnston defeated Thurmond 186,180 votes to 158,904 votes (54% to 46%). It was the only statewide election Thurmond would ever lose.

In 1952, Thurmond endorsed Republican Dwight Eisenhower for the Presidency, rather than Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson. This led state Democratic Party leaders to block Thurmond from receiving the nomination to the Senate in 1954, forcing him to run as a write-in candidate.

Senate career

1950s

In 1954 he became the only person ever elected to the U.S. Senate as a write-in candidate, campaigning, at the recommendation of Governor James Byrnes, on the pledge to face a contested primary in the future. He resigned in 1956, triggering an election. He then won the Democratic primary—in those days, the real contest in South Carolina—for the special election triggered by his own vacancy. His career in the Senate remained uninterrupted until his retirement 46 years later, despite his mid-career party switch.

Thurmond supported racial segregation with the longest filibuster ever conducted by a single senator, speaking for 24 hours and 18 minutes in an unsuccessful attempt to derail the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Cots were brought in from a nearby hotel for the legislators to sleep on while Thurmond rambled on about random things, including his grandmother's biscuit recipe. Other Southern senators, who had agreed as part of a compromise not to filibuster this bill, were upset with Thurmond because they thought his defiance made them look bad to their constituents.[7]

According to journalist Jeff Sharlet, he was a member of the Family (also known as the Fellowship), described by prominent evangelical Christians as one of the most politically well-connected fundamentalist organizations in the U.S.[8]

1960s

Throughout the 1960s, Thurmond generally received relatively low marks from the press and his fellow senators in the performance of his Senate duties, as he often missed votes and rarely proposed or sponsored noteworthy legislation.

Thurmond was increasingly at odds with the Democratic Party. On September 16, 1964, he switched his party affiliation to Republican. He played an important role in South Carolina's support for Republican presidential candidates Barry Goldwater in 1964 and Richard Nixon in 1968. South Carolina and other states of the Deep South had supported the Democrats in every national election from the end of Reconstruction to 1960. However, discontent with the Democrats' increasing support for civil rights resulted in John F. Kennedy barely winning the state in 1960. After Kennedy's assassination, Lyndon Johnson's strong support for the Civil Rights Act and integration angered white segregationists even more. Goldwater won South Carolina by a large margin in 1964.

In 1968, Richard Nixon ran the first GOP "Southern strategy" campaign appealing to disaffected southern white voters. Although segregationist Democrat George Wallace was on the ballot, Nixon ran slightly ahead of him and gained South Carolina's electoral votes. Due to the antagonism of white South Carolina voters towards the national Democratic Party, Hubert Humphrey received less than 30% of the total vote, carrying only majority black districts.

At the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, Thurmond played a key role in keeping Southern delegates committed to Nixon, despite the sudden last-minute entry of California Governor Ronald Reagan into the race. Thurmond also quieted conservative fears over rumors that Nixon planned to ask either Charles Percy or Mark Hatfield—liberal Republicans—to be his running mate, by making it known to Nixon that both men were unacceptable for the vice-presidency to the South. Nixon ultimately asked Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew—an acceptable choice to Thurmond—to join the ticket.

At this time, too, Thurmond took the lead in thwarting Lyndon Johnson's attempt to elevate Justice Abe Fortas to the post of chief justice of the United States. Thurmond's devotion to his conservatism had left him quite unhappy with the Warren Court, and he was happy simultaneously to disappoint Johnson and to leave the task of replacing Warren to Johnson's presidential successor, Richard Nixon.

Thurmond decried the Supreme Court opinion in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, which ordered the immediate desegregation of schools in the American South.[9] Thurmond praised President Nixon and his "Southern Strategy" of delaying desegregation, saying Nixon "stood with the South in this case."[9]

1970s

Thanks to his close relationship with the Nixon administration, Thurmond found himself in a position to deliver a great deal of federal money, appointments and projects to his state. With a like-minded president in the White House, Thurmond became a very effective power broker in Washington. His staffers said that he aimed to become South Carolina's "indispensable man" in D.C.

Post-1970 views regarding race

Thurmond supported extending the Voting Rights Act, making the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. a federal holiday.[2] He appointed African-American Thomas Moss to his staff in 1971, described as the first appointment by a member of the South Carolinian congressional delegation (also incorrectly reported by many sources as the first senatorial appointment of an African-American, but Mississippi Senator Pat Harrison hired clerk-librarian Jesse Nichols in 1937). Despite the actions, Thurmond never explicitly renounced his earlier views on racial segregation.[3][10][11][12]

Later career

Thurmond became President pro tempore in 1981, and held the largely ceremonial post for three terms, alternating with his longtime rival Robert Byrd depending on the party composition of the Senate. On December 5, 1996, Thurmond became the oldest serving member of the U.S. Senate, and on May 25, 1997, the longest serving member (41 years and 10 months). He cast his 15,000th vote in September 1998. He joined the minority of Republicans who voted for the Brady Bill.

Towards the end of Thurmond's Senate career, there was controversy over his mental condition. His supporters argued that while he lacked physical stamina due to his age, mentally he remained aware and attentive and maintained a very active work schedule in showing up for every floor vote. He stepped down as Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee at the beginning of 1999, as he had pledged to do in late 1997. Resignation of a sitting chairman, even an elderly one, was highly unusual in the Senate. (Term limits for committee chairs adopted by the Republican Conference only forced some turnover years later and were not at issue in this case.) The move suggested that Thurmond or his colleagues (or both) felt he was no longer capable of fulfilling that role.

Declining to seek re-election in 2002, he was succeeded by fellow Republican Lindsey Graham. Thurmond left the Senate in January 2003 as the United States' longest-serving senator (a record later surpassed surpassed by Senator Byrd). In his November farewell speech in the Senate, Thurmond told all his colleagues "I love all of you, especially your wives," the latter being a reference to his flirtatious nature with younger women. At his 100th birthday and retirement celebration in December, Thurmond stated "I don't know how to thank you. You're wonderful people, I appreciate you, appreciate what you've done for me, and may God allow you to live a long time." [13]

On June 26, 2003, he died at 9:45 p.m. of heart failure at the age of 100, at a hospital in Edgefield and is interred there in Willowbrook Cemetery.

Personal life

Marriages and children

Thurmond married his first wife, Jean Crouch (July 24, 1926 – January 6, 1960) in South Carolina's Governor's mansion on November 7, 1947. She died of cancer 13 years later; there were no children.

He married his second wife, Nancy Janice Moore (born 1946), Miss South Carolina of 1965, on December 22, 1968. He was 66 years old and she was only 22. She had been working in his Senate office off and on since 1967. It is often said that he ran for president before she was born. This is false; however, he was old enough to be eligible. They separated in 1991, but never divorced. The two remained married and close friends until his death. He even considered resigning during his last term, but only if the Governor would appoint his wife to the seat as his replacement.

At age 68 (with his wife Nancy at age 25) Thurmond fathered what was then believed to be his first child. His four children with Nancy are: beauty pageant contestant Nancy Moore Thurmond (1971–1993), who was killed when a drunk driver hit her in Columbia, South Carolina; former U.S. Attorney for the District of South Carolina and current South Carolina 2nd Judicial Circuit Solicitor James Strom Thurmond Jr. (born 1972);[14][15] Washington, D.C., homemaker Juliana Gertrude Thurmond Whitmer (born 1973);[16] and Charleston County, South Carolina, Council Member Paul Reynolds Thurmond (born 1976).[17]

Another daughter

Six months after Thurmond's death on June 26, 2003, Essie Mae Washington-Williams publicly revealed that she was Strom Thurmond's daughter. She was born to a black maid, Carrie "Tunch" Butler (1909–1948), on October 12, 1925, when Butler was 16 years old and Thurmond 22. He helped pay Washington-Williams' way through college and later paid her sums of money in cash or checks passed through relatives. Though Thurmond never publicly acknowledged Washington-Williams when he was alive, he continued to support her financially. These payments extended well into her adult life.[18] Washington-Williams has stated that she did not reveal she was Thurmond's daughter during his lifetime because it "wasn't to the advantage of either one of us"[18] and that she kept silent out of love and respect for her father.[5] She denies that there was an agreement between the two to keep her connection to Thurmond silent.[18]

After Washington-Williams came forward, the Thurmond family publicly acknowledged her parentage. Many close friends, staff members, and SC state residents had long suspected this to have been the case,[19] stating that Thurmond had always taken a great amount of interest in Washington-Williams and that she was granted a degree of access to Thurmond more appropriate to a family member than to a member of the public.[20]

Political timeline

- Governor of South Carolina (1947–1951)

- States' Rights Democratic presidential candidate (1948)

- Eight-term senator from South Carolina (December 1954 – April 1956 and November 1956 – January 2003)

- Democrat (1954 – April 1956 and November 1956 – September 1964)

- Republican (September 1964 – January 2003)

- President pro tempore (1981–1987; 1995 – January 3, 2001; January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2001)

- Set record for the longest one-man Congressional filibuster (1957)

- Set record for oldest serving member at 94 years (1997)

- Set the then-record for longest cumulative tenure in the Senate at 43 years (1997), increasing to 47 years, 6 months at his retirement in January 2003, surpassed by Robert Byrd in July 2006

- Became the only senator ever to serve at the age of 100

Electoral history

Legacy

- The Strom Thurmond Foundation, Inc. provides financial aid support to deserving South Carolina residents who demonstrate financial need. The Foundation was established in 1974 by Thurmond with honoraria received from speeches, donations from friends and family, and from other acts of generosity. It serves as a permanent testimony to his memory, and to his concern for the education of able students who have demonstrated financial need.

- Thurmond is mentioned in a 1993 Frasier episode entitled "Here's Looking at You." In the episode Frasiers' son Frederick is afraid that Thurmond is hiding in his bedroom closet.

- A reservoir on the Georgia–South Carolina border is named after him: Lake Strom Thurmond.

- The University of South Carolina is home to the Strom Thurmond Fitness Center, one of the largest fitness complexes on a college campus. The new complex has largely replaced the Blatt Fitness center, named for Solomon Blatt who was a political rival of Thurmond.

- Charleston Southern University has a Strom Thurmond Building, which houses the school's business offices, bookstore, and post office.

- Thurmond Building at Winthrop University is named for him. He served on Winthrop's Board of Trustees from 1936–38 and again from 1947–51 when he was governor of South Carolina.

- A statue of Strom Thurmond is located on the grounds of the South Carolina State Capitol as a memorial to his service to the state.

- Strom Thurmond High School is located in his hometown of Edgefield, South Carolina.

- The Rev. Al Sharpton was reported on February 24, 2007 to be a descendent of slaves owned by the Thurmond family. Sharpton has not asked for a DNA test.[21][22][23]

- The U.S. Air Force has a C-17 Globemaster named "The Spirit of Strom Thurmond".

- In 1989 he was presented with the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Ronald Reagan.

- In 1993 he was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George H. W. Bush.[24]

- The Strom Thurmond Institute is located on the campus of Clemson University. George H. W. Bush was on hand at the ground breaking ceremony while he was the Vice President.

- Appears in the 2008 award-winning documentary on Lee Atwater, Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story.

Notes

- ↑ "Robert Byrd to Become Longest-Serving Senator in History". Associated Press. June 11, 2006. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,199010,00.html. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Noah, Timothy. "The Legend of Strom's Remorse: a Washington Lie is Laid to Rest". Slate. http://www.slate.com/id/2075453/. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Stroud, Joseph (1998-07-12). "Dixiecrat Legacy: An end, a beginning". The Charlotte Observer. p. 1Y. http://www.slate.com/id/2075662. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ↑ "What About Byrd?". Slate. 2002-12-18. http://www.slate.com/id/2075662. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Thurmond's Family 'Acknowledges' Black Woman's Claim as Daughter". Associated Press. December 17, 2003. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,105820,00.html.

- ↑ Noah, Timothy (December 16, 2002). "The Legend of Strom's Remorse". Slate. http://slate.msn.com/?id=2075453. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ↑ Caro, Robert (2002). Master of the Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson, New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-52836-0

- ↑ Sharlet, Jeff (2008). The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power. HarperCollins. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-06-055979-3.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Woodward, Bob; Scott Armstrong (September 1979). The Brethren. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-24110-9. Page 56.

- ↑ "Strom Thurmond's Evolution". Lakeland Ledger. 1977-11-23. p. 6A. http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1347&dat=19771123&id=KL8SAAAAIBAJ&sjid=_PoDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2976,6847917. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ "What About Byrd?". Slate. 2002-12-18. http://www.slate.com/id/2075662. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ↑ "Jesse R. Nichols". http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/Nichols_preface.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ↑ "Thurmond marks 100th birthday". CNN. December 5, 2002. http://archives.cnn.com/2002/ALLPOLITICS/12/05/thurmond.birthday/index.html.

- ↑ See

- ↑ See

- ↑ See A. Juliana was the mother of Strom Thurmond's first grandchild B. See also C and D

- ↑ Elected to the Council in 2006.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 60 Minutes interview, December 17, 2003

- ↑ Janofsky, Michael (December 16, 2003). "Thurmond Kin Acknowledge Black Daughter". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/16/national/16STRO.html?ex=1231218000&en=0509c5d87e66cd7a&ei=5070.

- ↑ http://http://www.frankkwheaton.com/uploads/INTRODUCTORY_REMARKS.pdf

- ↑ Interview with Al Sharpton, David Shankbone, Wikinews, December 3, 2007.

- ↑ "Slavery links families". New York Daily News. February 25, 2007. http://www.nydailynews.com/front/story/500577p-422090c.html.

- ↑ Santos, Fernanda (2007-02-26). "Sharpton Learns His Forebears Were Thurmonds’ Slaves". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/26/nyregion/26sharpton.html?n=Top/Reference/Times%20Topics/People/T/Thurmond,%20Strom&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2007-11-26

- ↑ Reed, John Shelton (June 1, 1993). "Strom Thurmond and the Politics of Southern Change". Reason. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Strom+Thurmond+and+the+Politics+of+Southern+Change.-a014113205. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Further reading

- Finley, Keith M. Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965 (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2008).

- "Abe Fortas: A Biography," by Laura Kalman: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Dear Senator: A Memoir by the Daughter of Strom Thurmond by Essie Mae Washington-Williams, William Stadiem: Regan Books (February 1, 2005). ISBN 0-06-076095-8.

- The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968 by Kari Frederickson: University of North Carolina Press (March 26, 2001). ISBN 0-8078-4910-3.

- "The Faith We Have Not Kept," by Strom Thurmond: Viewpoint Books, 1968.

- Ol' Strom: An Unauthorized Biography of Strom Thurmond by Jack Bass, Marilyn Walser Thompson: University of South Carolina Press (January 1, 2003). ISBN 1-57003-514-8.

- Strom: The Complicated Personal and Political Life of Strom Thurmond by Jack Bass and Marilyn Walser Thompson: Public Affairs 2005. ISBN 1-58648-297-1.

- Strom Thurmond & the Politics of Southern Change by Nadine Cohodas: Mercer University Press (December 1, 1994). ISBN 0-86554-446-8.

External links

- Strom Thurmond Institute at Clemson University

- U.S. Senate historical page on Strom Thurmond

- SCIway Biography of Strom Thurmond

- NGA Biography of Strom Thurmond

- Oral History Interview with Strom Thurmond from Oral Histories of the American South

- Strom Thurmond Foundation, Inc.

- Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Citizens Medal - January 18, 1989

Articles

- Strom Thurmond's family confirms paternity claim, By David Mattingly, CNN.com, December 15, 2003

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Voting record maintained by The Washington Post

- The Scarred Stone: The Strom Thurmond Monument by Joseph Crespino, Emory University, 29 April 2010

Obituaries

- Tribute to Strom Thurmond from The State — June 26, 2003

- Strom Thurmond dead at 100 at the Wayback Machine (archived June 29, 2003)., CNN, June 26, 2003

- Strom Thurmond Dead at 100, By James Di Liberto Jr., Fox News, June 26, 2003

- Strom Thurmond at Find a Grave Retrieved on 2008-08-04

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ransome Judson Williams |

Governor of South Carolina 1947–1951 |

Succeeded by James F. Byrnes |

| Preceded by Ted Kennedy Massachusetts |

Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee 1981–1987 |

Succeeded by Joe Biden Delaware |

| Preceded by Warren Magnuson Washington |

President pro tempore of the United States Senate January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1987 |

Succeeded by John C. Stennis Mississippi |

| Preceded by Sam Nunn Georgia |

Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee 1995–1999 |

Succeeded by John Warner Virginia |

| Preceded by Robert Byrd West Virginia |

President pro tempore of the United States Senate January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2001 |

Succeeded by Robert Byrd West Virginia |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2001 |

||

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Charles E. Daniel |

United States Senator (Class 2) from South Carolina December 24, 1954 – April 4, 1956 Served alongside: Olin Johnston |

Succeeded by Thomas A. Wofford |

| Preceded by Thomas A. Wofford |

United States Senator (Class 2) from South Carolina November 7, 1956 – January 3, 2003 Served alongside: Olin Johnston, Donald S. Russell, Ernest Hollings |

Succeeded by Lindsey Graham |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by None |

Dixiecrat Presidential Candidate 1948 |

Succeeded by None |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by John C. Stennis Mississippi |

Dean of the United States Senate January 3, 1989 – January 3, 2003 |

Succeeded by Robert Byrd West Virginia |

| New title | President pro tempore emeritus of the United States Senate June 6, 2001 – January 3, 2003 |

|

| Preceded by Jennings Randolph |

Oldest living U.S. Senator May 8, 1998 – June 26, 2003 |

Succeeded by Hiram Fong |

| Preceded by Jimmie Davis |

Oldest living U.S. governor 2000–2003 |

Succeeded by Luis A. Ferré |

| Preceded by Charles Poletti |

Earliest serving US governor 2002–2003 |

Succeeded by Sid McMath |

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||